Human beings have defined education very broadly for thousands of years. One of the oldest concepts of education, found in diverse human societies around the globe, has been the idea of "enlightenment."

From our earliest records, human beings have explained education in terms of illuminating the darkness of the human condition, overcoming fear of the unknown through the light of human understanding, which paves the way for liberation and purposive action (often against the oppressive power of the gods, kings or social institutions). In the tradition that I was raised, the western concept of enlightenment can be traced to the very origins of philosophy in Ancient Greece.

Later in the 17th and 18th centuries, European philosophers referred to their time as an "age of enlightenment" because they were expanding the horizons of human knowledge through both a rediscovery of ancient knowledge and through new forms of intellectual inquiry that would be called science. Then in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European and American philosophers re-examined the ancient western conceptions of enlightenment in conjunction with the early developments of modern science, while at the same time discovering other ancient traditions of human enlightenment found in eastern and middle-eastern philosophy from China, India, Persia, Palestine, and Japan.

During the 20th century, the western world had more sustained and reciprocal cultural contact with eastern cultures and their traditions of knowledge. This cultural exchange enabled eastern philosophers, poets, and religious teachers to have a larger impact on western philosophy through translations of eastern texts and also through direct contact, as many European scientists visited the Asian sub-continent and some eastern mystics and philosophers began to visit Europe and America.

The 20th century also saw scientists from around the globe asking classically philosophical questions about the nature of reality and the human condition, thus, redrawing the boundaries of human knowledge by using a wide array of empirical data and modern scientific theories.

At the dawn of the 21st century we have access to an unprecedented amount of knowledge, three thousand years of global philosophy and several hundred years of empirical scientific study. The challenge for 21st century education is synthesizing the diverse traditions of global knowledge about the human condition into a coherent intellectual framework. One way of doing this is by focusing back on the ancient idea of enlightenment and critically analyzing it in relation to the past three thousand years of human history.

At the center of the ancient concept of enlightenment are three interrelated ideas: (1) clarifying human perception, (2) knowing the "real" world as accurately as possible, and (3) using this knowledge to freely act, thereby living more successfully and meaningfully.

At root the concept of enlightenment equates knowledge of reality with human freedom. The idea is that more complete knowledge of reality enables individuals to disentangle from restrictive determinants in order to more freely and completely act. Furthermore, the enlightenment of the individual is often assumed to advance the goals and harmony of human society, which would ultimately lead to a "perfect" utopian culture.

John Gray calls this later goal "the Enlightenment project," which historically has been a deep-set religious impulse of Europe and America, whereby people have placed faith in the unlimited capacity for human perfection and material progress.1

From the earliest historical records, people have been asking a recurring set of perennial questions: What is reality? How do we know? How shall we live together? What does it mean to be human?

I want to attempt to give a short, critical history of the concept of enlightenment, which I think provides a broad, coherent, multicultural, and meaningful key to understanding the promise of education for the 21st century. An educational philosophy based on the principle of enlightenment would encourage not only the pursuit of knowledge, but also the possibility of increased freedom. It would also warn people about the various constraints of being human that limit our freedom and our knowledge, the understanding of which would help enable a more pragmatic ideal of human possibility.

For most of human history the cosmos of the known universe was populated by deities and devils in a simplistically ordered whole, which we now refer to as myths. As Henry Adams poetically noted, "Chaos was the law of nature; order was the dream of man."2 Across the globe, humans acted in broad ignorance of the objective world, mixing local intelligence and tradition with fanciful belief in the power of magic, prayer, and fate.

Human beings seemed to have some small measure of power over their lives, but they were often at the mercy of the larger physical environment and chaotic natural processes, which were beyond comprehension, yet alone human control. Mythological stories of gods, spirits, and heroes enabled humans to make some sense of a world they couldn't really know, and these stories gave human beings meaning and hope, which enabled them to survive and eventually thrive.

Early philosophers in ancient Greece, and later in the Roman imperium, began to challenge some of these myths through dialogue and critical reasoning, but these ancient intellectuals had little evidence to actually convince people.3 Socrates (c 469-399 BCE) was perhaps the most famous example. He argued that humans should admit when they are ignorant,4 they should debate the nature of reality, and they should "test the truth" of all ideas.5

Socrates was eventually condemned to death because he upset his society by questioning the gods and the traditional explanations of the cosmos, but even at his trial he was without remorse: "I say that it is the greatest good for a man to discuss virtue every day...conversing and testing myself and others, for the unexamined life is not worth living."6 Socrates' student Plato (428-347 BCE) famously extended this central insight into a parable about a cave. In this story, the enlightened philosopher realizes individuals are bound to cultural truths, which turn out to be nothing but manipulations, shadows on a wall. So, the philosopher escapes the cave and becomes enlightened by the sunny real world, which symbolizes the actual truth of existence.7

Several ancient eastern philosophers also criticized the myths of society and encouraged people to critically evaluate their perceptions to understand the deeper truths of reality. In ancient India, Gautama Buddha (c 563-483 BCE) taught that "this world has become blinded" because the average person's perception was "polluted." Only a few could "see insightfully." He taught his followers to "make a lamp for yourself," to purify their vision, and to "become a wise one" by "knowing full well, the mind well freed."8 A later follower of the Buddha described the central teaching of Buddhism as self-knowledge, which incidentally was also the core teaching of Socrates: "When the cloud of ignorance disappears, the infinity of the heavens is manifested, where we see for the first time into the nature of our own being."9

A contemporary of the Buddha in ancient China also developed a tradition of enlightenment. The philosopher K'ung Fu-tzu (c 551-479 BCE), we know him in the west as Confucius, tried to teach his students "insight" by "understand[ing] through dark silence." He encouraged his students to "study as if you'll never know enough, as if you're afraid of losing it all."10 A later follower, Meng Tzu (c 372-289 BCE) or Mencius, told a story about the revered master and his dedication to knowledge:

Adept Kung asked Confucius, "And are you a great sage, Master?

"I couldn't make such a claim," replied Confucius. "I learn relentlessly and teach relentlessly, that's all.

At this, Adept Kung said, "To learn relentlessly is wisdom, and to teach relentlessly is Humanity. To master wisdom and Humanity - isn't that to be a sage?"11

Confucius always pleaded a profound ignorance about life, as did Socrates, who famously claimed, "All I know is that I know nothing."

For Socrates, Buddha, Confucius, and Mencius, the root of human wisdom was to "relentlessly" learn and teach, perfecting the art of human living through a constant dedication to the practice of education, all the while professing a profound humility about the knowledge and wisdom they actually possessed.12 As philosopher Owen Flanagan has summarized:

“In separate places between the fourth and sixth centuries BCE, Plato and the Buddha describe the human predicament as involving living in darkness or in dreamland - amid shadows and illusions. The aim is to gain wisdom, to see things truthfully, and this is depicted by both as involving finding the place where things are properly illuminated and thus seen as they really are.”13

These ancient teachers lived their own philosophies and tried to embody wisdom. They also preserved a cannon of traditional texts that taught about the enlightened actions of gods, heroes, and sages. They wanted to teach not only about knowledge, but also a better way of life.

While the old epistemology of myth and tradition was questioned by a long line of western and eastern philosophers,14 it was not completely challenged until the birth of western science. However, early modern scientists displayed a continuity with ancient wisdom in the continued focus on enlightenment, albeit a new form of enlightenment based on new epistemological methods. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) and Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) ushered in what has been called the “Copernican” revolution with the “new art of experimental science.” This new science allowed a new type of truth to be fashioned based on empirical observation, innovative technology (like the telescope), experimentation, and mathematical theory.15

At the same time philosophers of science developed new scientific methods to logically explore and confirm a new type of truth based on logic and empirical evidence.16 Francis Bacon (1561-1626) popularized inductive logic and Rene Descartes (1596-1650) developed physical reductionism and analytical geometry.17 Isaac Newton (1643-1727) unified these developments, creating modern science by synthesizing experimental empiricism with more effective logical methods. He not only developed the calculus, in conjunction with the German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), but Newton also further developed the application of mathematical logic to the study of the physical world. Newton unequivocally replaced the divinely governed geocentric chain of being with a new empirical conception of heliocentric universe governed by natural laws. Newton wanted "to define the motions" of all physical objects "by exact laws allowing of convenient calculation.”18

As the Newtonian revolution reached across Europe it inspired many philosophers to conduct wide-ranging empirical studies of the natural world and human society. This period of European history was called the "age of enlightenment" by various philosophers of that era.19 By the end of the 18th century, the popularity of the term was criticized by Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). In an essay written in 1784, Kant asked "What is Enlightenment?" He explained that many human beings had finally reached a state of intellectual maturity, whereby they were able understand the world and themselves through direct evidence and without recourse to myths or traditions.

While the majority of humans were still mired down by "laziness and cowardice," there were a brave few who were "think[ing] for [them]selves," "cultivating their spirit," developing "rational" thought, and spreading the "spirit of freedom." Kant argued that Europeans were not living "in an enlightened age," but they were living in "an age of enlightenment," by which he meant an age where humans were gradually becoming more and more enlightened. Kant believed that if the ethos of this age were allowed to run its course, it would slowly spread to the public at large, although he was skeptical about whether the "great unthinking masses" could ever get beyond their subjective "prejudices" and achieve "a true reform in one's way of thinking."20

By the 19th century, both Newton’s theoretical methods and his belief in rationally ordered natural laws spread across Europe and America, as more and more philosophers and early scientists empirically studied the physical and social world. Most of these enlightened Europeans thought they could collect and assemble a vast array of empirical data, which would thereby transparently reveal the secret workings of Newton's rational laws.

These early scientists believed that a small number of hidden natural laws ordered and determined not only the physical universe, but also human society and individual action. The invention of the Encyclopedia in the 18th century embodied this simple assumption, as it was based on medieval compilations which purported to contain all the knowledge a person needed to know, like the Bible and the Speculum Mundi.21 For over a millennium, the learned men of Europe thought one book could hold everything a society needed to know. The new scientific literature merely replaced the Bible as the single source of intellectual and moral authority, but it did not challenge the simplistic monism of a transparent natural law.

This assumption of transparent, rational, transcendent, natural laws would stand unchallenged until the late 19th and early 20th century. During this time two later scientific revolutions corrected Newton's simplified view of the world and ushered in a new, more fruitful and frightful age of enlightenment. The great revolution in science during the 19th century was Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) theory of natural selection, which has been called “evolution.”

Darwin’s theory delivered a crippling blow to both anthropocentric beliefs about the uniqueness of human beings as a species and to deep set assumptions of the "progressive" advancement of human civilization. As the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche explained, Darwin was able to "translate man back into nature."22 Darwin helped historicize and naturalize human knowledge, as most people still believed in timeless supernatural forces to be the source of all change on Earth.

Basically, Darwin’s theory of natural selection described all life metaphorically as a dense interconnected tree. The trunk represented a primordial common ancestor of all life on Earth, which over billions of years branched out into millions of new forms through a process of blind, natural selection. New organisms arise due to random genetic modification over long periods of time as they struggle to adapt to changing environments. Certain modifications are “naturally selected” by the external environment because these random changes allow the organism to better survive, mate, and reproduce.23

Darwin’s theory enabled not only a “new science,” giving rise to fields like ecology and evolutionary biology, but it also created a “new way of thinking,” which focused on the dense interconnection, interdependence, and historically conditioned form of all life on Earth.24 Ernst Mayer claimed that Darwin “caused a greater upheaval in man’s thinking than any other scientific advance since the rebirth of science in the Renaissance.”25 I. Bernard Cohen, a pioneering historian of science, argued, “The Darwinian revolution was probably the most significant revolution that has ever occurred in the sciences.”

Its effects and influences were significant in many different areas of thought and belief. The consequence of this revolution was a systematic rethinking of the nature of the world, of man, and of human institutions. The Darwinian revolution entailed new views of the world as a dynamic and evolving, rather than static, system, and of human society as developing in an evolutionary pattern…The new Darwinian outlook denied any cosmic teleology and held that evolution is not a process leading to a “better” or “more perfect” type but rather a series of stages in which reproductive success occurs in individuals with characters best suited to the particular conditions of their environment – and so also for societies.26

Darwin’s “dangerous idea” completely naturalized and secularized the known world, completing the dream of Socrates and the Buddha, as the long assault on metaphysical belief finally rendered obsolete all notions of an "enchanted cosmos."27

However, modern advances in science have not completely unraveled the mystery of the physical universe. In fact, the most recent scientific revolution has unveiled a strange, unpredictable cosmos filled with wondrous and frightening possibilities. Quantum theory and quantum mechanics ushered in the unsettling notions of relativity and probability. The Newtonian framework of physical science was based on the idea of a limited number of absolute laws of the universe that determined all matter and motion in discrete, observable, and rational patterns.

But Albert Einstein’s (1879-1955) theory of relativity and Werner Heisenberg's (1901-1976) theory of quantum mechanics (and more recent developments in string theory) would revise the Newtonian assumption of simple laws and predicable patterns of motion, although many of these patterns seem to hold for the largest bodies of observable phenomena, like planets and solar systems.

Instead of a discrete, well-ordered universe of rational laws, Heisenberg discovered that physical matter at its most basic level is dynamic, chaotic, random, and wholly uncertain. Physicists are still debating the very nature, and thereby the names, of the building blocks of life. Because the physical universe is in constant chaotic motion and the exact position or course of any sub-atomic particle uncertain, the vantage-point of any subjective observer plays a role in trying to objectively observe, record, and understand data.

The implications of this revolution disordered basic scientific assumptions, such as objectivity, physical laws, predictability, and positive forms of knowledge. Even Einstein was concerned about his own discoveries, later in his life turning toward a unifying theory of everything because he believed that “God does not play dice with the universe.”28

But Einstein’s later reaction represented the last throws of an old Western belief in a fundamental order to reality that was both unchanging and discretely knowable. As David Lindley explained, "Heisenberg didn't introduce uncertainty into science. What he changed, and profoundly so, was its very nature and meaning. It had always seemed a vanquishable foe...The bottom line, at any rate, seems to be that facts are not the simple, hard things they were supposed to be."29

There is a new, profound truth that physical and social scientists are finally coming to terms with. The objective world that we inhabit is not singular, nor is it governed by simplistic and unchanging laws that determine everything according to a singular metaphysical clockwork. Further, in the wake Gödel's thesis and the Church-Turing thesis, scientists have had to admit that not every facet of reality is amenable to human intelligence.30

Even more so than Darwin's theory of natural selection, the idea of uncertainty has been perhaps the most profound and disquieting discovery in human history. The irrational and ingrained assumption of a singular, simplistic, and immutable order of the universe was not only the “great myth” of the ancient world, but it was also the “central dogma” at the foundation of the Western Enlightenment and the birth of modern science.

From the ancient Greek, Chinese, and Indian sages to the modern world of science, philosophers and scientists have believed in a "fundamental" principle of rational "order."31 Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the first philosophers to call this monistic belief in a rational order "a metaphysical faith," which Nietzsche connected to "a faith millennia old, the Christian faith, which was also Plato's, that God is truth, that truth is divine."32

According to philosopher and historian of science Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997), “One of the deepest assumptions of Western political thought is the doctrine, scarcely questioned during its long ascendancy, that there exists some single principle which not only regulates the course of the sun and the stars, but prescribes their proper behavior to all animate creatures…This doctrine, in one version or another, has dominated European thought since Plato…This unifying monistic pattern is at the very heart of the traditional rationalism, religious and atheistic, metaphysical and scientific, transcendental and naturalistic, that has been characteristic of Western civilization.”33

The breakdown of traditional monistic sources of authority began with the political philosophy of Niccolo dei Machiavelli (1469-1527) and was later questioned by counter-Enlightenment romantic philosophers. But it was not until the late 19th century, and more fully during the 20th century, that the assumed singular “Truth” of human rationality was fatally assaulted and finally pronounced dead by a tradition of radical European philosophers, from Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) and Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) to Michel Foucault (1926-1984) and Jacques Derrida (1930-2004). This European strain of philosophy also impacted and co-existed with an American school of thought called Pragmatism, which argued against singular truths in favor of epistemological and ontological plurality, from William James (1842-1910) and George Herbert Mead (1863-1931) to John Dewey (1859-1952) and Richard Rorty (1931-2007).

Upon closer examination, the myth of a singular, immutable physical Law proved to be no less quaint than the geocentric conception of the universe or the belief in a singular omniscient deity that sat at the edge of reality manipulating the strings of myriad human marionettes. It was only in the last century, and really in the past twenty-five years, that this myth of a singular order of the universe has been fully exposed as false - although many scientists still cling to this assumption. Discussing the aim of science in 1957, Karl Popper admitted, "the conditions obtaining almost everywhere in the universe make the discovery of structural laws of the kind we are seeking - and thus the attainment of 'scientific knowledge' - almost impossible."34

Many physical scientists (although not all) 35 now admit that reality is not a singular, static system governed by universal laws. Instead, the objective world is understood as a complex, interdependent ecology composed of multiple dynamic levels, with many complex systems continually producing emergent qualities that are difficult to understand because they are more than the sum of their parts.36 The physical world is a complex "open system" composed of "pluralistic" domains, which are in interrelated and in constant flux.37 Some have ceased calling the total expanse of reality the universe and instead refer to it as a "multiverse."38

This notion of a complex web of interdependent life was acknowledged by Darwin in the 1860s and later caused a paradigm shift in the physical and social sciences beginning in the 1890s.39 Henry Adams noted the breakdown of the old order and the beginning of a new, more chaotic universe at the turn of the 20th century.40 However, the older monistic paradigm continues to be a powerful assumption, as it has only been partially eliminated from current scientific theory and practice.41

The old notion of "universal laws," assumed by classical scientists, has largely been proven a fiction that does not accurately describe the physical world.42 For some scientists, the over-turning of this old dogma is tantamount to a "crisis of faith."43 Over the past century there has been a widespread acknowledgement of the "delusion of the universal," which has led to a "re-conceptualization of science."44

Based on a broad reading of scientific discoveries over the full range of physical, biological, and human sciences, it is clear that the objective world consists of multiple, interrelated, interdependent, fluctuating, and evolving levels of reality: from the smallest elements at the sub-atomic level to the atomic level, the molecular level, the chemical level, leading up to the organism level, ranging from very simple to very complex organisms, to various biological social-groups which compose larger societies, to the many ecosystems across the planet, to the global level, to our solar system, and to the larger galactic systems all the way to the edge of the expanding universe.45 The Nobel Prize winning chemist Ilya Prigogine is one of many 20th century scientists who recognized the inherent plurality of the objective world: "Nature speaks with a thousand voices, and we have only begun to listen."46

Various possible languages and points of view about the system may be complementary. They all deal with the same reality, but it is impossible to reduce them to one single description. The irreducible plurality of perspectives on the same reality expresses the impossibility of a divine point of view from which the whole of reality is visible...emphasizing the wealth of reality, which overflows any single language, any single logical structure. Each language can express only part of reality.47

In order to be studied, the objective world has to be broken down into these many conceptual levels of analysis (and even many dimensions of space and time, as string theorists have been arguing), each with their own special properties and emergent functions, co-existing in a dense ecological web of life. Each level needs its own "regional theory,"48 with accompanying analytical concepts and methods, which are all analytical fictions that scientists create to practically label and know an isolated part of dense interconnected reality that is not entirely knowable, let alone predictable or controllable.49

All levels and dimensions of this dense web of reality are connected together and dependent upon each other, deriving their very substance out of the complex interplay of invisibly interwoven ecological relationships. Most of the levels and dimensions of the objective world cannot be directly perceived by the human mind and we rely on complex technologies to catch a glimpse. Some of these levels and dimensions cannot even be fathomed, let alone conceptualized into a coherent theory, as string theorists are dealing with at the sub-atomic level. As Alan Lightman pointed out, "We are living in a universe incalculable by science."50

As a species, we do not have the innate capacities to fully conceive, let alone know the complex reality of the objective world in its totality. It is completely beyond us, and perhaps always will be unless we can develop some kind of super technology that will enhance our cognitive abilities. This is a profound truth that most scientists have not yet fully acknowledged, as many practicing scientists seem to believe that humans have an unlimited capacity for rationality, knowledge, and technological progress.51

We need to constantly remind ourselves, in the words of Paul Ricoeur, that humanity is both an "exalted subject" and a "humiliated subject."52 Human beings are not gods with infinite powers of reason and will. They are in fact quite limited in their abilities to know and freely act. And when humans do act, they are often animated by various motivations and ideals that conflict with each other, forcing hard decisions over which good should prevail.

We are also continually plagued by the unforeseen consequences of our short-sided decisions. This old notion of human limits was the bedrock of many conservative philosophers and the literary genre of tragedy: from Sophocles (497-406 BCE) and Euripides (480-406 BCE) to Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE) and St. Augustine (354-430 CE) to Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) and Edmund Burke (1729-1797) up to contemporary thinkers Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997) and John Gray (1948-).

All of these insightful philosophers, in the most expansive sense of this term, warned against transgressing traditional boundaries out of a blind pride in human knowledge and will.53 And this notion of human limits is not confined to conservative thought. There has also been a tragic strain of liberalism that questions the complexity of reality, the conflicting diversity of human goods, and the constraints bounding human rationality.54 For most of human history there has been widespread doubt about the ability of human beings to understand and control the social and physical environment, which would be the foundation of what we call "freedom." The ancient Greeks even used a special word for those who dared to defy the traditional order of the universe and try to freely act, hubris.

But with the development of critical philosophy, and later, the methods of logic and the empirical sciences, humans began to believe that they possessed special powers that could overcome inherent limitations of the species and the rest of the biological world. And to some extent, with the new tools of science and technology, they did. Thus, using a revised concept of enlightenment, 18th and 19th century philosophers believed that increased knowledge would allow humans to control the natural world and their own destiny. This was the dream of early modern science and the European age of enlightenment. John Gray notes that this philosophy of human progress was a "secular version" of the Christian faith it sought to replace.55

The great apotheosis of this belief in human rationality and progress came in the philosophy of Georg W. F. Hegel (1770-1831). He believed that there was a fundamental "rational process" to the natural world. This rationality slowly revealed itself through history via the unique creation of human beings who gradually perfected their ability to know and freely act: "The History of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of Freedom...we know that all men absolutely (man as man) are free."56 This lead Hegel to famously claim that "What is rational is actual and what is actual is rational," by which he meant whatever exists is rational and right and must be accepted as the inherent unfolding of universal laws that unequivocally govern all life - laws which just so happen to have expressed themselves through the progressive perfection of human beings and human society.57

But as already discussed, the universe turned out to be much more complex and stranger than humans had always imagined it, and human beings turned out to be much more flawed than enlightenment philosophers assumed. Thus, in the 20th century, modern intellectuals had to revise the older optimistic vision of enlightenment humanism to deal with the very real biological, social, and physical constraints of the human condition, not the least of which was admitting the savage, self-destructive capabilities of human beings. Far from a progressive unfolding of rationality and freedom, as Hegel suggested, the 20th century seemed to ominously hint that humans might utterly destroy themselves and their planet.

Early in the century the Irish poet W. B. Yeats warned that the "ceremony of innocence" of enlightenment humanism would be "drowned" because the "blood-dimmed tide" of human irrationalism had been "loosed" upon the world. Human beings were revealing their true nature as "rough beast[s]" whose self-inflicted apocalypse had "come round at last."58 Later, in the midst of the second World War, the

English poet W. H. Auden noted that "Evil is unspectacular and always human."59 The 20th century would remind humans of their animal nature ("human, all too human," as Nietzsche sighed60), which gave rise to another form of frightful uncertainty. If humanity did not have the capacity for enlightenment and freedom, then what hope for a better world?

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was one of the most profound 20th century philosophers who dealt with the paradoxical predicament of eclipsed enlightenment principles in the "post-modern" world. In an unpublished manuscript Foucault revisited the classic essay of Immanuel Kant and asked again, "What is enlightenment?" Foucault started by noting that Kant had used the German word Aufklarung, which was a way of saying an "exit" or a "way out," by which Kant had meant a way out of the limitations of a traditional humanity ruled by irrational myths and the cruelty of our animal instincts. Kant wanted humans to "escape" from tradition and human imperfection, to "dare to know," and thereby to create the condition for enlightenment and human freedom which were yet still only ideals.

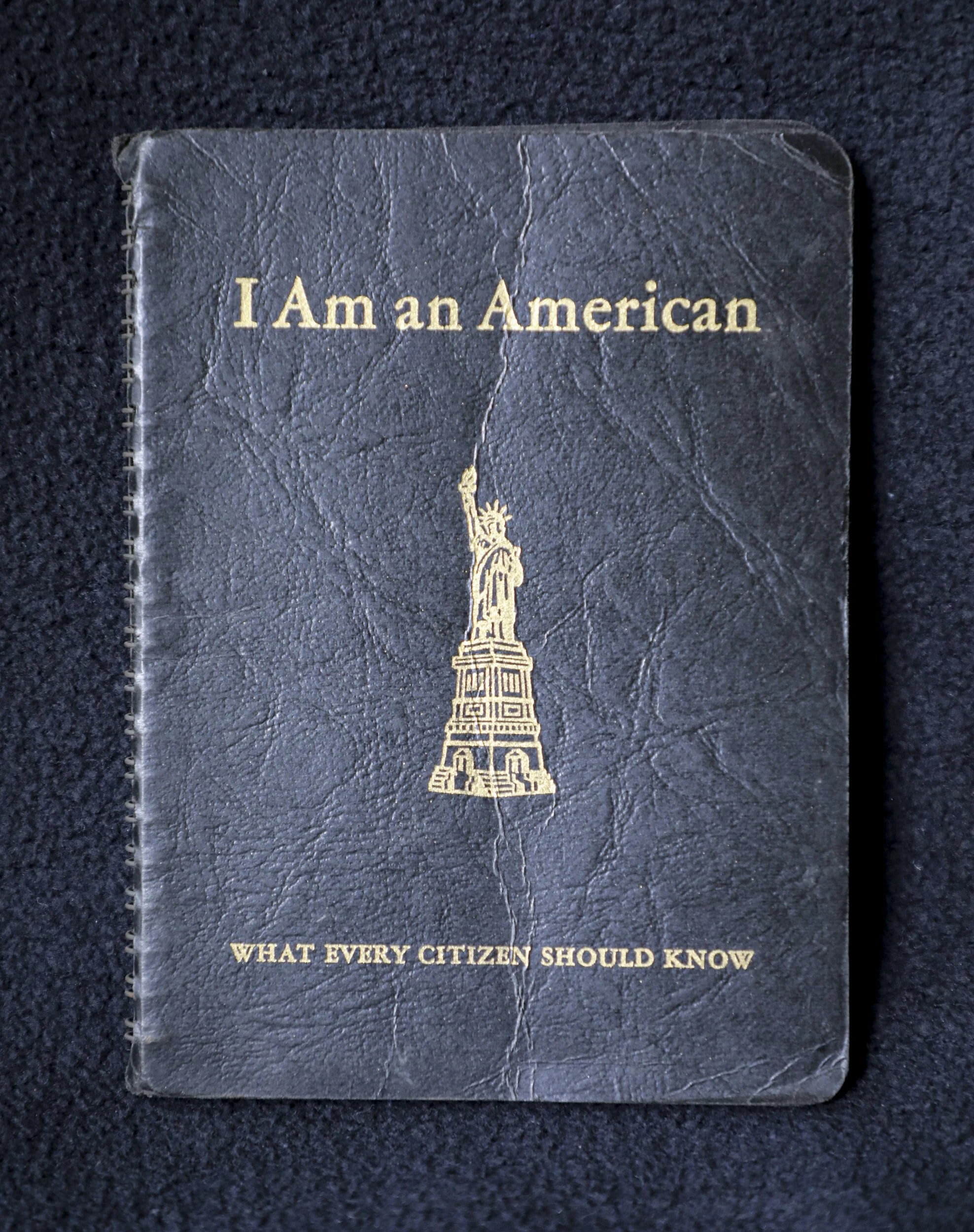

The implications of this directive were at once personal and also social. Human freedom would take not only an individual act of will, but also a political revolution to free humans from the "despotism" of traditional sources of authority.61 This led philosopher Allan Bloom to declare that the European enlightenment was the "first philosophically inspired 'movement'" that was both "a theoretical school" and a "political force at the same time."62

Yet Kant was not a revolutionary and he was very distrustful of the notion of democracy. At the same time that Kant had written his essay, enlightenment notions of human freedom inspired an unprecedented wave of democratic revolutions that would sweep the globe.63 The principles of enlightenment meant "political activism" and "the transformation of society," the basic tenets of progressivism, or the political Left.64 Radicals like Thomas Paine believed that we as human beings "have it in our power to begin the world over again."65

The first enlightenment inspired revolution happened in the North American English colonies. The founding fathers of the United States of America saw themselves as an enlightened vanguard who were "spreading light and knowledge" to the rest of the world. They wanted to defeat the tyranny of monarchical despotism and free themselves to fulfill the promise of enlightenment principles.66 John Adams (1735-1826) saw America as "the opening of a grand scene and design in Providence for the illumination of the ignorant, and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind all over the earth."67 Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) declared that "all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights; that among these are life, liberty & the pursuit of happiness."68

These ideas spread across the globe and inspired oppressed people yearning to be free. One notable group of young European intellectuals in the early 19th century were especially inspired by these enlightenment ideals. They were called the Young Hegelians, after their famous teacher Georg W.F. Hegel. Believing in Hegel's theory of a progressive rational order in human history, this group of radical philosophers wanted to put enlightenment principles into practice in order to revolutionize the whole world, giving freedom and knowledge to all people.69 The most famous and influential intellectual among this group was Karl Marx (1818-1883). He argued, "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it."70 In order to change the world, Marx introduced what he saw as the intellectual and political culmination of Hegel's world-spirit (Weltgeist) of enlightenment humanism.

This would be a philosophy Marx called "communism," which he saw as "the solution of the riddle of history."71 Harkening back to both Hegel and to older notions of eastern enlightenment, Marx wanted a "reform of consciousness."72 He wanted human beings to "give up their illusions about their condition" and to "give up a condition that requires illusions."73 Marx and his later followers, taking a page from the American and French revolutions, wanted to use science and technology to free the exploited peoples of the world, both intellectually and politically, so as to create a global utopia of free and enlightened human beings.

But the 20th century saw the corruption and destruction of this radical social and political hope.74 The rapid increase in scientific knowledge and technology, as John Gray has pointed out, left the human species "as they have always been - weak, savage and in thrall to every kind of fantasy and delusion."75 The revolutionary spirit of American and French democracy (among others) was blocked and slowly aborted by entrenched conservative elites and the manipulation and coercion of the uneducated masses (and in the French case, the use of terror), all of which led enlightenment humanists to latch their progressive idealism onto authoritarian autocrats or illiberal bureaucratic states.76 Marx's revolutionary socialism and the revolt of the proletariat smashed naively and recklessly across the world, devolving into fascism, authoritarian states,77 and various ethnic holocausts.78

Also, the very notions of western enlightenment and human freedom were desecrated by the vicious global imperialism of Europe and America. These global empires plundered the riches of the world and subjugated the majority of the people on Earth, leaving most humans as little more than colonial slaves, and then these empires stood back as former colonies devolved into perpetual war and genocide.79 Finally, by mid-century, the two dominant empires on the earth were locked in a Cold War with nuclear weapons on hair triggers, threatening to destroy all life on Earth in assured mutual destruction.80

During the long 20th century, the ancient dream of enlightenment seemed to have been shredded at the cruel hands of a barbarous humanity tearing itself to pieces.81 One Jewish survivor of the Nazi death camp Auschwitz argued that humans would have to admit that they live in "a monstrous world, that monsters do exist" and that "along-side of [enlightenment] Cartesian logic there existed the logic of the [Nazi] SS": "It happened [the holocaust], therefore it can happen again."82 Lawrence L. Langer declared, "the idea of human dignity could never be the same again."83

In revisiting the simplicity of Kant's text on enlightenment, Michel Foucault asked whether or not a great existential "rupture" had taken place in the 20th century. Foucault questioned Kant's idea of intellectual maturity and doubted that humans could ever reach this state. While humans had more knowledge about themselves and their world, it was a "limited" and "always partial" knowledge. Foucault argued that we needed to give up the notion of "complete and definitive knowledge," and instead we needed to focus on how we have been shaped by historical circumstance and how we have acted upon those circumstances within certain "limits." Foucault wanted to more fully understand the constraints and possibilities of the human condition. But with this notion of limited knowledge and action, Foucault cautioned that we must not lose our "faith in Enlightenment" because as an ideal it pushes us to know more, to better ourselves, and to try to better our society.84

Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997) agreed with this revised version of enlightenment. Berlin argued that our knowledge of the world and of ourselves in the late 20th century brought about two basic truths: reality is much more complex than we ever imagined, and we as human beings are much more flawed than we ever before admitted. Berlin explained that there was "too much that we do not know" and that "our wills and the means at our disposal may not be efficacious enough to overcome these unknown factors."85

As Friedrich Nietzsche once pondered, "When you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you."86 The developing practice of science had brought about great gains in knowledge and technology, but it had also further enabled the brutal tendencies of human beings to destroy themselves and their environment. Our great increase in knowledge and technology has not enabled greater human freedom for most people, nor has it solved the intractable problems of our paradoxical nature and society.87 The history of human folly has not ended, as some idealistic philosophers have assumed.88

In the early 20th century, one of the most educated and technologically advanced human societies caused a global war and engineered the efficient murder of millions. Writing just before the Nazis democratically rose to power, Sigmund Freud was very pessimistic concerning human beings’ ability to use knowledge and technology toward noble ends in an effort rise above our biological constraints: "Men have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in exterminating one another to the last man."89

About a century later, John Gray came to the same conclusion: "If anything about the present century is certain, it is that the power conferred on 'humanity' by new technologies will be used to commit atrocious crimes against it."90 After World War II and the horrors of the holocaust, Raymond Aron caustically pointed out that humans would "like to escape from their history, a 'great' history written in letters of blood. But others, by the hundreds of millions, are taking it up for the first time, or coming back to it."91 In his moral history of the 20th century, Jonathan Glover forcefully emphasized that "we need to look hard and clearly at some monsters inside us."92

At the start of the 21st century humans face not only continuing warfare, poverty, disease, and outbreaks of genocide, but also a new looming catastrophe, the environmental destruction of the planet, which could actually bring out Freud's fateful apocalypse, the extinction of the entire human species.93 John Gray went so far as to call humans a "plague animal" and all but warned that our demise as a species was imminent.94 Amartya Sen, on the other hand, has acknowledged the great strides humanity has taken since the atrocities of the first and second World Wars, while noting that we still "live in a world with remarkable deprivation, destitution and oppression."95

Surveying previous human societies that have destroyed themselves, geologist Jared Diamond said he remains a "cautious optimist" on the capacity of human beings in the 21st century to learn from the past in order to solve the looming environmental crisis and the socio-political upheaval it will cause. He explained, "we have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of distant peoples and past peoples. That's an opportunity that no past society enjoyed to such a degree."96

Given the tragedy of the 20th century, I would agree with Foucault that the concept of enlightenment needs to be revised. As John Gray has perceptively pointed out, "We live today amid the dim ruins of the Enlightenment project, which was the ruling project of the modern period."97 We now realize that enlightenment is not blind faith in knowledge combined with the false hope of unlimited progress. Instead, we must focus on the constrained possibilities and limitations of being human, which includes our limited capacity to know, act, and shape our world. Some philosophers call this position of limited freedom a "soft determinism."98

The philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm (1900-1980) explained the new promise of this revised concept of enlightenment: "We are determined by forces outside of our conscious selves, and by passions and interests which direct us behind our backs. Inasmuch as this is the case, we are not free. But we can emerge from this bondage and enlarge the realm of freedom by becoming fully aware of reality, and hence of necessity, by giving up illusions, and by transforming ourselves from somnambulistic, unfree, determined, dependent, passive persons into awakened, aware, active, independent ones."99 It is important to note that Fromm said "enlarge the realm of freedom" instead of perpetuating the naive myth of being completely free to determine our destiny in any way we please.

Recent scientific discoveries in cognitive psychology, sociology, evolutionary psychology, and socio-biology lend credence to this new concept of enlightenment as limited rationality and constrained freedom, which was developed philosophically in the 20th century by Foucault, Berlin, and Fromm, among others. The philosopher of science Daniel C. Dennett argues that modern science has proven a biological, social, and environmental determinism that shapes and constrains both individual action and human society. He also argues that fundamentally life is essentially chaotic and "random," which means that humans have limited predictive powers to understand the present and plan for the future.

John Gray has taken these facts to an extreme and argued that humans are just "deluded animals" because they "think they are free, conscious beings."100 But determinism and chance do not entirely rule out freedom and volition, they just circumscribe it. "Free will is real," Dennett claims, "but it is not a preexisting feature of our existence, like the law of gravity. It is also not what tradition declares it to be: a God-like power to exempt oneself from the causal fabric of the physical world. It is an evolved creation of human activity and beliefs, and it is just as real as such other human creations as music and money."

Free will exists because we as humans believe it to exist and we act according to this belief, just like we believe that certain kinds of colored paper allow us to purchase goods and services - not because of any inherent property in ourselves (or in the colored paper), but because we say it exists, believe it exists, and institutionally structure our society around this belief. We do have the power to alter our reality through ideas.101

But our capacity for free will is also grounded in our biology from which we will never entirely escape.102 We know that much of who we are as humans, including our behavior, it largely determined by our genes. But as Matt Ridley pointed out, "Genes are often thought of as constraints on the adaptability of human behavior. The reverse is true. They do not constrain; they enable."103 As a species we are uniquely endowed with the ability to learn and enhance our lives with knowledge and technology collectively stored in our culture.

We have evolved from an animal-like state into what Dennett calls "informavores," "epistemically hungry seekers of information."104 We use this information to create knowledge, which in turn is used to better understand our world and improve our condition. While we are biologically, socially and environmentally determined, our human nature is not fixed. We can change. Not only can we use information to change our environment, but we can also build tools, like eye glasses, penicillin or computers, that compensate for biological deficiencies or maladies and give us greater power over our human nature.105 This is the realm of human culture, which separates us from all other species of life on Earth.106

Sigmund Freud famously called humans a "kind of prosthetic God," due to our technological advances over our environment and our biological bodies.107 Karl Popper believed that human evolution in the 20th century was being driven not by biology anymore but by technology.108 Some scientists studying our human genes argue that we will be able to soon manipulate the very building blocks of our biology, allowing for a new "directed evolution."109 Other scientists in the field of cybernetics and artificial intelligence are even trying to create a new kind of human, blending technology into our biology to produce the "cyborg" and the "human-machine civilization," which they optimistically say promises not only greater knowledge and freedom, but also immortality.110

E. O. Wilson has claimed that mastering our genetic code could bring a new form of "volitional evolution," which would allow humans to be "godlike" and "take control" of our "ultimate fate."111 Mark Lynas has gone so far as to call us "the God species."112 While their visions might vary, all of these Cornucopian idealists believe in a form of "technofideism," i.e. a "blind faith" that innovative technology will solve all of the world's problems.113 Francis Fukuyama bluntly declared, "Technology makes possible the limitless accumulation of wealth, and thus the satisfaction of an ever-expanding set of human desires."114

The economist Julian Simon believes "the material conditions of life will continue to get better for most people, in most countries, most of the time, indefinitely."115 The marvel of current technological wonders aside, the verdict is still out on just how far technology can take us as a species. But one thing is sure, technology is no panacea for all of the human-created problems on planet Earth, let alone naturally occurring problems, like earthquakes, hurricanes, volcanoes, and the odd asteroid smashing into our planet.

But these idealistic visions of human grandeur are not entirely misconceived. Even though we are determined as a species, like all other biological organisms on this planet, our unique evolutionary adaptations and cultural development have enabled "a degree of freedom," which we can exploit for our own improvement. Language, abstract thought, and culture in particular are tools unique to human beings.116 How far we can change is dependent on many factors: our personal knowledge and experience, our vast store of cultural knowledge, the advancement of our technology, and our environment, which includes both physical resources and constraints, and also social resources and constraints, like access to money and political power.

Rene Dubos pointed out, "Man's ability to transform his life by social evolution and especially by social revolutions thus stands in sharp contrast to the conservatism of the social insects, which can change their ways only through the extremely slow processes of biological evolution."117 Thus, we can use our language, our critical thinking, and a vast store of cultural and physical resources to partially create ourselves and our social reality, albeit within certain fixed biological, physical, and social limits.118

Perhaps science and technology might push those limits farther than we can now imagine, but there will always be limits. Naively believing that science and technology will erase those limits is a "modern fantasy."119 Knowledge is freedom, that much is true. However, due to the "imperfect rationality" and constrained abilities of our species, caused by various determining factors in our biology and environment, ours will forever be a bounded, limited and imperfect freedom.120

Thus, we need to re-conceive the concept of enlightenment and human nature through a more biological and ecological understanding of physical life in terms of "nature via nurture."121 The physicist Fritjof Capra has pointed out, "cognition is the very process of life...Cognition...is not a representation of an independently existing world, but rather a continual bringing forth of a world through the process of living...'To live is to know.'"122

This insight has led some scientists, like the entomologist Edward O. Wilson, the philosopher Daniel C. Dennett, and the cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker, to argue that it is time to revisit the ancient notion of "human nature" in order to formulate "a realistic, biologically informed humanism," which combined with our knowledge of human culture would be the newest phase of human enlightenment.123 At the center of our biological nature is the process of cognition, how we know: "reasoning, intelligence, imagination, and creativity are forms of information processing." But we as humans do not know in isolation, we utilize other people and our culture, which is "a pool of technological and social innovations that people accumulate to help them live their lives...culture is a tool for living."124

We need to understand how our brain "evolved fallible yet intelligent mechanisms" to perceive and understand reality, as discussed in the first chapter of this book. We also need to understand how the "world is a heterogeneous place," and how we as humans are "equipped with different kinds of intuitions and logics" to apprehend and understand different aspects of reality. There is no one way to know, just like there is no one thing to know.

One of the most important ways of knowing is through the tool we call an "idea," which is a complex network of meaningful information put into language that we use to better know our world and to more wisely act. Human beings are a species "that literally lives by the power of ideas."125 Philosophers merely extend this "personal commitment to ideas" a bit further than the average human, but the practice of philosophy is inherent trait that all human beings share (whether they consciously realize this or not).126

We need to also realize that we are not always in complete control of our ideas or the technologies they enable. Ideas have a tangible, objective reality that make them a constitutive part of human culture and subjectivity.127 Many ideas grow beyond the mind of their originator, spread to other minds, and evolve through particular cultures through historical processes to become what social scientists call "institutions."128 Institutions are the self-evident and often taken for granted social structures, both ideological and organizational, found within particular human societies. The social structure of an institution can be described as the organized ideas and procedures that pattern particular social practices.129 These institutional procedures can also be described as the "working rules" governing a particular social practice,130 which can be thought of as a "rule-structured situation."131

While we do create our own ideas and institutions, at some point they begin to take on a life of their own and create us. The early historical-sociologists, Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Max Weber, each studied different social structures of constituting rule systems in Western society. They wanted to understand the underlying logics that established and maintained the modern world: the social, political, economic, and religious rules, organizations, procedures, rituals, and ideas that ordered societies. Recent institutional theorists have complicated older notions of institutions, which were often overly simplistic and monistic, because we now know that institutions are “rich structures” of diverse, overlapping, and often conflicting patterns of social practice.132

The concept of social institutions hurdles a social-scientific dualism that has been unresolved for the past century. At the center of the social sciences has been a central debate over how societies and social institutions are constituted and how they change. Societies and social institution can be seen, on the one hand, as the “product of human design” and the outcome of “purposive” human action. However, they can also be seen as the “result of human activity,” but “not necessarily the product of conscious design.” One of the paradigmatic examples of this dualism is language. Human beings are born speaking a particular language with pre-defined words and a pre-designed grammar; however, individual human beings are also able to adopt new languages, create new words, and change the existing definition of words or grammatical structures.

But is any individual or group of individuals in conscious control of any particular language? The obvious answer is no, but each individual has some measure of effect, yet just how much effect is subject to debate. For the past quarter century or so, scholars have rejected the idea that societies, institutions, and organizations can be reduced to the rational decisions of individuals, although purposive individuals do play a role. The new theory of institutions focuses on larger units of analysis, like social groups and organizations “that cannot be reduced to aggregations or direct consequences of individual’s attributes or motives.” Individuals do constitute and perpetuate social structures and institutions, but they do so not as completely or as freely as they believe.133

The new institutional theory has focused mainly on how social organizations have been the locus of “institutionalization,” which is the formation and perpetuation of social institutions. While groups of human beings create and sustain social organizations, these organizations develop through time into structures that resist individual human control. Organizations also take on a life of their own that sometimes defies the intentions of those human beings directing the organization. While institutions can sometimes begin with the rational planning of individuals, the preservation and stability of institutions through “path dependent” processes (what we generally call “history”) is often predicated on ritualized routines, social conventions, norms, and myths.

Once an institution becomes “institutionalized,” the social structure perpetuates a “stickiness” that makes the structure “resistant” to change. Individual human actors, thereby, become enveloped and controlled by the organization’s self-reinforcing social norms, rules, and explanatory myths, which are solidified through positive feedback mechanisms that transcend any particular human individual. These organizational phenomena, thereby, shape individual human perception, constrain individual agency, and constitute individual action.

As one institutional theorist has argued, all human “actors and their interests are institutionally constructed.” To a certain extent humans do create institutions and organizations, but more immediately over the course of history, institutions and organizations create us. Many millions of individuals have consciously shaped the English language, but as a child I was constituted as an English-speaking person without my knowledge or consent. It is perhaps more accurate to say that English allowed for the creation of my individuality than it is to say that my individual subjectivity shaped the institution of English.134

But if all human thought and action is constituted by previously existing institutions, do human beings really have any freedom to shape their lives or change society? This is actually a very hard question to answer and it has been the center of many scientific debates over the past century. Durkheim and Parsons seemed to solidify a sociology that left no room for individual volition. Marx stressed human control, but seemed to put agency in the hands of groups, not individuals. Weber discussed the possibility of individual agency, especially for charismatic leaders, but he emphasized how human volition was always “caged” by institutions and social organizations. Michel Foucault conceptualized human beings as almost enslaved by the various modern institutions of prisons, schools, and professions.135

The novelist Henry Miller brilliantly expressed the predicament of human agency, whereby his knowledge of himself and society failed to enable any real freedom: "I see that I am no better, that I am even a little worse, because I saw more clearly than they ever did and yet remained powerless to alter my life."136 Taking stock of all of the possible arguments for human freedom, the philosopher Thomas Nagel explained, "The area of genuine agency...seems to shrink under this scrutiny to an extensionless point. Everything seems to result from the combined influence of factors, antecedent and posterior to action, that are not within the agent's control."137

The enlightenment notion of unencumbered individual freedom was deconstructed during the 20th century and revealed to be nothing but a myth. However, some recent neo-institutional theorists have recently left open the possibility of individual rationality and freedom, albeit in a limited and constrained form. Human agency sometimes defined as the mediation, manipulation, and sometimes modification of existing institutions. Pierre Bourdieu argued that there was a "dialectical relationship" between institutional structures and individuals.138 Human beings can act in concert with institutions or against them, and individuals can also refuse institutionalized norms and procedures, thereby, highlighting another type of agency.

Humans can also exploit contradictions between different institutional structures, and use one institution to modify another.139 Ronald L. Jepperson argues that there can be “degrees of institutionalization” as well as institutional “contradictions” with environmental conditions. This means that certain institutions can be “relative[ly] vulnerab[le] to social intervention” at particular historical junctures. Jepperson is one of the few institutional analysts who conceptualize a theory of human action and institutional change, which allows for “deinstitutionalization” and “reinstitutionalization.” But Jepperson does not validate rational choice theories of individual agency. He argues instead that “actors cannot be represented as foundational elements of social structure” because their identity and “interests are highly institutional in their origins.”

However, this position does not disavow institutionally mediated individual choice and action. As Walter W. Powell has argued, “individual preferences and choices cannot be understood apart from the larger cultural setting and historical period in which they are embedded,” but individual actors have some freedom within institutional environments to “use institutionalized rules and accounts to further their own ends.” Roger Friedland and Robert R. Alford argue that “the meaning and relevance of symbols may be contested, even as they are shared.” “Constraints,” Powell paradoxically argued in one essay, “open up possibilities at the same time as they restrict or deny others.”140

The anthropologist Sherry B. Ortner has developed a comprehensive theory of human agency that allows individuals more power to consciously participate in, and thereby, shape and modify institutions. She describes the individual agent in a “relationship” with social structures. This relationship can be “transformative” on both parties: each acts and shapes the other. While the individual is enveloped by social structures, there is a “politics of agency,” where individual actors can become “differentially empowered” within the layered “web of relations” that make up the constraints of culture. Individuals can act through a process of reflexivity, resistance, and bricolage.

Humans use an awareness of subjectivity and negotiate their acceptance and refusal of the status quo. Through this process, humans can re-create existing social structures by reforming traditional practices and also by introducing novel practices. Ortner conceptualized the process of agency as the playing of “serious games,” utilizing a metaphor originally deployed by the analytical philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. She argued forcefully that existing cultural structures and social reproduction is “never total, always imperfect, and vulnerable,” which constantly leaves open the possibility of “social transformation” to those who dare to act out against the status quo.141

However, researchers have pointed out that those who are moderately alienated or marginalized from existing institutions seem to have a greater chance of imagining new institutional forms and acting against existing institutional power: "Those at the peripheries of the system, where institutions are less consolidated, are more likely to discover opportunities for effective opposition and innovation...Change is more likely to be generated by the marginally marginalized, the most advantaged of the disadvantaged."142

Recent scholarship has also emphasized how organizations and institutions are structured within "particular ecological and cultural environments."143 Looking at the wider sphere of organizational ecology allows researchers to understand how individuals and social organizations are interconnected within a dense social web. Interdependent social groups interact with each other to mutually shape the physical and social environment, which in turn impacts the evolution of organizations, organizational forms, and institutionalized practices and norms.144 Organizations are mutually influenced by a host of social sectors, including nation-states, geographical regions, local governments, other organizations, and micro social groups, like the family and peer networks.145

Within each sector there are diverse “clusters of norms” and organizational typologies that institutionally define and constrain individual and organizational actors, and thereby, a host of institutional norms and forms are continually reified and perpetuated across a diversely populated social and organizational landscape, which slowly changes through time. Because societies are characterized by such diversity of social sectors, each with their own institutions and norms, different institutions can be “potentially contradictory,” which can allow for social conflict and social change through time as institutions develop in relation with the institutional and physical environment.146

However, it is still unclear how institutions “change” and what change actually means. Theorizing the nature and extent of institutional change is an unresolved issue. Institutions are seen as stable social structures outside the control of rational agents which seem to slowly adapt to internal and environmental conditions through an incremental process, although there is some evidence to suggest that rapid changes can occur in short periods due to environmental shocks.147 Due to the contingent and evolving complexity of human institutions, one economist acknowledged, "We may have to be satisfied with an understanding of the complexity of structures and a capacity to expect a broad pattern of outcomes from a structure rather than a precise point prediction."148

Because human institutions are embedded within dense webs of social and physical ecologies, it is hard to study their complexity utilizing the simplistic theories of traditional academic disciplines. As the Nobel Prize winning Economist Elinor Ostrom pointed out, "Every social science discipline or subdiscipline uses a different language for key terms and focuses on different levels of explanation as the 'proper' way to understand behavior and outcomes," thus, "one can understand why discourse may resemble a Tower of Babel rather than a cumulative body of knowledge."149

The only way forward is to break down artificial disciplinary boundaries in order to "integrate the natural sciences with the social sciences and humanities" into a unified body of knowledge,150 which is something that Ostrom has tried to do with her Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework.151 This new interdisciplinary way of knowing would focus on physical, biological, and social structures that enable and constrain human beings in specific historical contexts.152 Our current notion of human enlightenment is still based on the foundational idea that "knowledge is the ultimate emancipator," as Edward O. Wilson recently put it.153 In fact, Wilson consciously linked the goals of 21st century science with the older notions of enlightenment humanism, as he invoked its underlying ethos, "We must know, we will know."154

But our new age of enlightenment needs to be grounded by an understanding of both the complexity of knowledge and also the epistemological limitations of human beings. Wilson acknowledges that the "immensurable dynamic relationships" between different types of organisms, and also different levels of reality combined with the "exponential increase in complexity" between lower levels of reality and higher levels of reality, all pose the "greatest obstacle" to a unified human knowledge.

It is extremely hard (if not ultimately impossible) to get "accurate and complete description of complex systems."155 On top of this, human knowledge needs to be grounded in the new sciences of the human mind (cognitive science and epistemology) because "everything that we know and can ever know about existence is created there."156 At the root of these new sciences is our "humbling" realization that "reality was not constructed to be easily grasped by the human mind," thus, we need to know both what can and cannot be known and also how to live better without perfect knowledge.157

I completely agree with Wilson's socio-biological explanation of human nature and cognition, including his arguments on how genes condition knowledge and the structure of society;158 however, I disagree with Wilson's assertion that the old enlightenment myth of "reductionism" and physical "laws" will be central to 21st century science and a unified field of knowledge. Wilson and a great many other scientists still believe that "nature is organized by simple universal laws of physics to which all other laws and principles can eventually be reduced." Although it must be noted that Wilson is exceptional in his humility, admitting that this fiction of universal laws is at least "an oversimplification" of the complexity of reality, and further, "it could be wrong."159

While I am willing to admit that there are some physical laws, I think it has already been readily established that even physical laws are constant only in specific spatial-temporal environments, leading to what Pierre Bourdieu called "regional theories," or what Bernard Williams called "local perspectives."160 Physicists now understand that different levels of reality have their own rules,161 and the validity of these rules are explained by "effective theories," which can only effectively explain a specific level of reality and nothing more.162

Einstein theoretically proved that both time, space, and gravity can bend, which alters the constant properties of each, therefore, even these "constants" are not all that constant throughout the universe. Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman later discovered that some other assumed theoretical constants seem "to vary from place to place within the universe."163 At the smallest most fundamental level of reality, the sub-atomic level, there does not appear to be any governing laws at all. It appears to be complete chaos, which is paradoxical given the ordered complexity of the chemical level up through the planetary level.164

Thus, the laws of physics may be multitudinous across a vast universe that we have only begun to understand;165 however, this does not mean that there are "a total absence of reliable rules" governing reality.166 We just can't assume that the rules controlling one level of reality will be valid at a higher or lower level of complexity.167 While I would agree with biologists that evolution is a "law" that governs the process of change in all organisms and even human societies here on the planet Earth, I think it would be foolish to say that sub-atomic particles or solar systems are bound by this same principle of natural selection, although perhaps this theory might still have explanatory power for the level of solar systems.168

Over the course of the 20th century there has been a clear move away from "rigidly deterministic and mono-causal models of explanation" towards more a more complex understanding of the diverse nature of reality.169 We must get away from universal "laws" and instead look for the overlapping or layered "regional theories" that approximate the various levels and processes determining physical reality. Elinor Ostrom has argued that human culture and institutions have "several layers of universal components," which means that "multiple levels of analysis" are needed to fully explain the complex ecology of any social practice.170 There are also many layers to the physical world, ranging from the infinitely small sub-atomic particles through the many layers of the biological world to the large realm of planets and galaxies. Each level of reality that has been identified by scientists is an area of specialization with its own name, terminology and methods of analysis.171

As the Physicist and philosopher David Deutsche pointed out, multiple disciplinary frameworks reflect the underlying complexity of the physical world and they cannot be collapsed into a single reductionist framework: "None of these areas of knowledge can possibly subsume all the others. Each of them has logical implications for the others, but not all the implications can be stated, for they are emergent properties of the other theories' domains."172 It is especially important to understand that higher orders of more complex life cannot be reduced to the simpler base components of lower levels because there is an "emergence" of higher order properties that have their own unique dynamics. As biologist Ernst Mayr pointed out, "In each higher system, characteristics emerge that could not have been predicted from a knowledge of the components."173

We must guard against scientists with valid regional theories in one domain of reality who encroach on other domains, especially scientists who seek to reduce higher order systems to the simpler function of lower order parts. David M. Kreps has explained this phenomenon as a form of epistemological "imperialism."174 A theory that might be valid on one level of reality can easily become invalid by distorting another level of reality it cannot comprehend.

For example, while I agree with biologists and socio-biologists that both humans and human societies evolve, I completely disagree with many physical scientists over the mechanism of evolution in human culture. The zoologist and socio-biologist Richard Dawkins famously reduced human beings to genes and reduced human culture to "memes" as biological "structures" of cultural transmission.175

Quite literally, Dawkins theorized that our bodies and our ideas replicate independently of human intention: "It is not success that makes good genes. It is good genes that make success, and nothing an individual does during its lifetime has any effect whatever upon its genes."176 Likewise, Dawkins argued that human ideas can be reduced to memes, which are a form of social gene, where "replicators will tend to take over, and start a new kind of evolution of their own."177 Thus, human beings are merely passive incubators for genes and memes. Nothing more, nothing less.

This notion has been widely accepted in both scholarly and popular circles,178 but it is naively absurd,179 and it merely proves my point about extending valid scientific theories beyond their corresponding level of reality. While the mechanism of natural selection on genes does explain most of human biological evolution, this theory is not valid or insightful when extended to social phenomenon, where intentional human actors purposively affect their own lives and cultures (to a certain extent).

John Gray has pointed out, "Biology is an appropriate model for the recurring cycles of animal species, but not for the self-transforming generations of human beings."180 Likewise, the evolutionary biologist and geologist Jared Diamond conclusively demonstrated that "our rise to humanity was not directly proportional to the changes in our genes."181 Further, Diamond warned, "While sociobiology is thus useful for understanding the evolutionary context of human social behavior, this approach still shouldn't be pushed too far. The goal of all human activity can't be reduced to the leaving of descendants."182

To illustrate this obvious point, one needs to look no further than Dawkins own mother. She once explained to Dawkins when he was a boy that "our nerve cells are the telephone wires of the body."183 Now if human communication is nothing but a blind and random biological transmission of memes, then how does Dawkins purposefully remember this meaningful story after so many years? And if human communication can be reduced to electrical impulses and memes, then where did the meaning of this story come from.

Further, how am I able to take this story out of context to change the meaning in order to criticize Dawkins for being an absurd reductionist? While the reality and importance of genes cannot be discounted, many scientists arrogantly believe that "hard" quantitative sciences, like chemistry or socio-biology, are the best (and often the only) way to understand human beings and our culture. This arrogant reductionism is often called "scientism."184 The "question of meaning" cannot be answered by physical science, which is not to say that meaning and the human mind are metaphysical entities.185 Both meaning and the mind are physical and social realities grounded in and facilitated by the empirical world, but that empirical world is very complex and one cannot simply reduce higher order psychological and social phenomena to chemical or genetic processes.

Because they discount the reality of social and psychological ecologies, such reductionists also never bother to think about individual and social consequences of reductionist theories, such as memes.186 The notion that "nothing an individual does during its lifetime has any effect whatever upon its genes" can be easily translated into a pernicious form of nihilism, leading to individual paralysis and social anarchy.187 Such reductionism ignores the reality of the "culture gap" between us and all other species on Earth.188

While we are physical beings programmed and constrained by natural laws, like all other organic organisms on this planet, the homo-sapien is a very unique creature that has also created a subjective world through consciousness and society, which has its own emergent properties and governing structure. Culture exists and is every bit as important as genes in terms of shaping our behavior as a species, yet socio-biologists like Wilson and Dawkins miss this important level of reality because of their reductionist scope.

Many physical scientists, especially in the relatively new fields of socio-biology and evolutionary psychology, have been drunk on their particular methodology and the scientific success it has enabled. Seeking to imperially expand their explanatory power, these physical scientists inevitably ride rough with their simplistic reductionism through the complexities of human life and culture. The analytical concept of genes is important, but ultimately only one small part of the complex puzzle of life. Richard Dawkins wants us to believe that "the gene's perspective" is the most important, valid and insightful uber-perspective of all.189